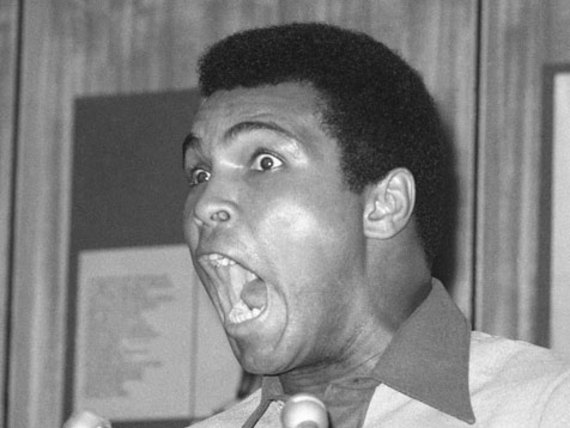

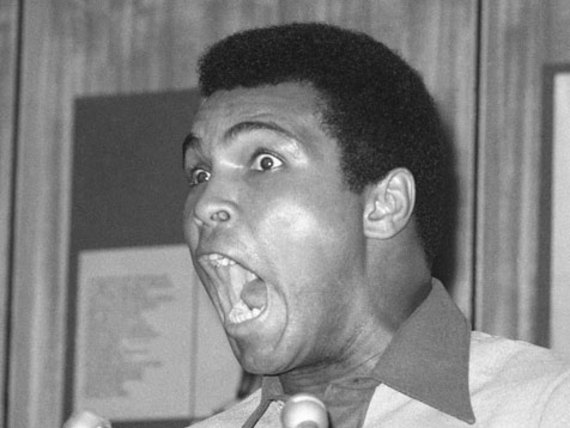

Cassius Marcellus Clay. The “Lousiville Lip”. “The Greatest” heavyweight boxing champ of all time. “Floated like a butterfly, stung like a bee!” My second boyhood hero… long before he became known as the most famous man on the planet, Muhammad Ali. In 1960, when i was 13 years old, 18 year old Cassius Clay burst onto the national sports scene by winning the Olympic gold medal. He was brash. Talented. Faster than lightning. And he couldn’t be beat. With the help of loud mouth and equally-brazen sportscaster, Howard Cosell, Clay brought entertainment, poetry, and show biz back to the dismal sport of boxing in the 1960s. We middle class white kids loved him. People of all colors and creeds loved him. And by 1964, he was fighting the dark, brooding heavyweight champ, Sonny Liston, “The Bear” for the world title. February 25, 1964. Miami beach, Florida. Sports Illustrated magazine called it one of the 4 greatest moments in sports of the 20th century… when the brazen, 22 year old Cassius Clay seemed to be hysterically blinded by something on Liston’s gloves in the 4th round, yet only 3 rounds later, had the invincible Liston failing to answer the bell for the 7th round. “I shook up the world. I shook up the world. I must be the greatest,” Clay screamed at the press corps after the fight, and every one of us hero-worshipping kids agreed whole-heartedly.

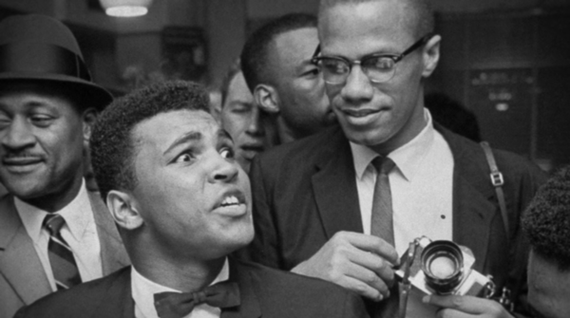

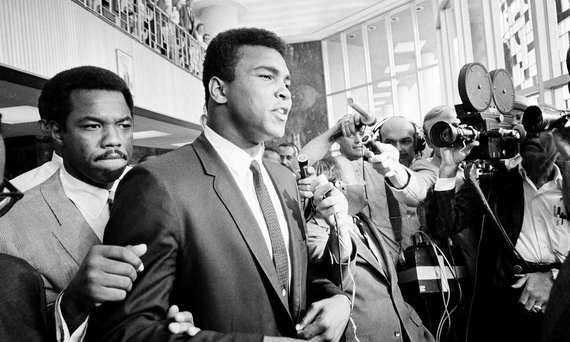

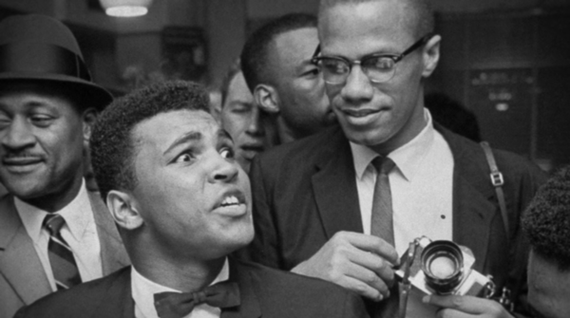

Two days later, Clay shocked us all again, by announcing he was a “Black Muslim”, a member of the feared “Nation of Islam”. He was a devotee of its leader, Elijah Muhammad (who just days later would give him his Muslim moniker, “Muhammad Ali”), and a personal friend of Malcolm X, the verbally-acute firebrand, who would be assassinated only a year later, by three members of the Nation of Islam, which Malcolm had repudiated as too conservative. Civil rights and “black power” were in full force in 1965, and Ali now insisted that the press call him by his new Black Muslim name, not by his slave name, “Clay”.

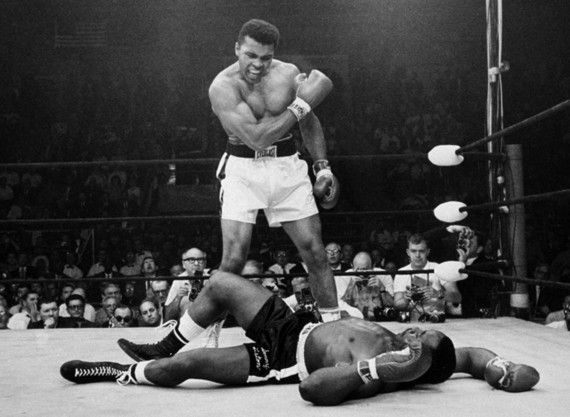

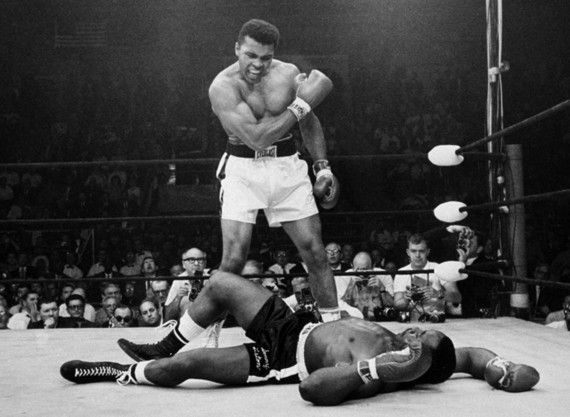

Overnight, the white press and its nationwide readership were frightened by this new champ. But not me. I remember the 2nd Liston-now Ali fight, May, 1965. My family was taking an early summer vacation in Lake George, New York, and I was sitting by myself in our 1960 Chevy Impalla station wagon out in the rain, listening to the radio broadcast from Lewiston, Maine. It was even more fantastic and unbelievable than the first fight, as Liston hit the deck and stayed down for the count… in the first round… from a “phantom punch” that Ali threw… that nobody saw. Just like Mickey Mantle, my first boyhood hero, Muhammad Ali, in just two championship fights, elevated himself to the stuff of legend.

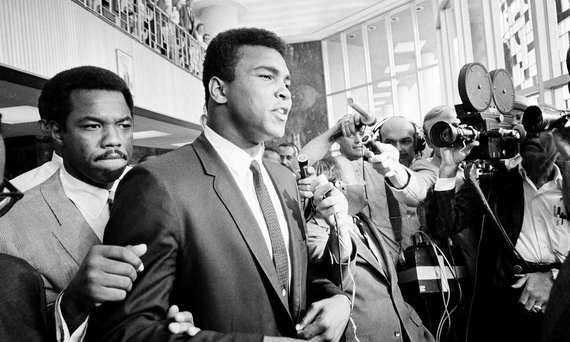

After that, me and my college roommate, Ric Reaper, saw every one of Ali’s heavyweight fights… albeit almost entirely on closed circuit, giant tv screens, in sports arenas in Buffalo, New York, where we went to college, and where we saw Ali take out ex-champ, Floyd “The Rabbit” Patterson, and “bums of the month” like British champ, Henry Cooper, powerfully-muscled Cleveland Williams, and rangy Ernie Terrell, who Ali taunted in the ring with shouts of “What’s my name, Uncle Tom? What’s my name?” For me and The Reaper, Ali could do no wrong… whether in the ring… or out. Then, we were stunned when, in 1967, our sophomore years, Ali was stripped of his title for refusing to be inducted into the U.S. armed forces, stating publicly that, “no Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

He claimed exemption from military service based on his Islamic religious beliefs and on grounds of being a conscientious objector, yet was systematically denied a boxing license in every state in the union and stripped of his passport. He did not fight from March 1967 to October 1970—from ages 25 to almost 29—at the height of his pugilistic powers, as his case worked its way through the appeal process. During this time, Ali made the rounds speaking on college campus around the country, and of course, me and The Reaper were there in the 3rd row when he came to SUNY Buffalo in 1968. We have cherished photos of ourselves with “The Champ” from that day, but we knew it must have been hard for Ali to survive without boxing during this time.

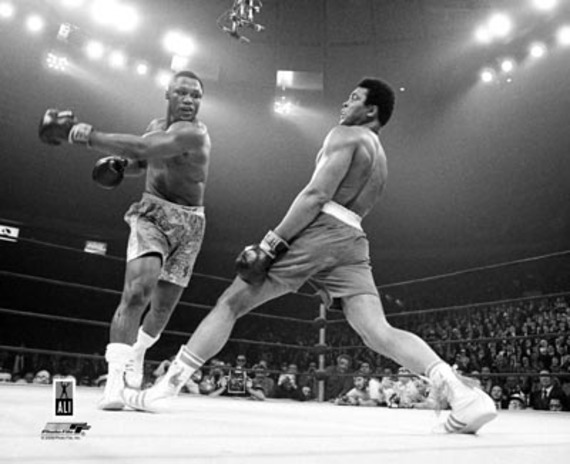

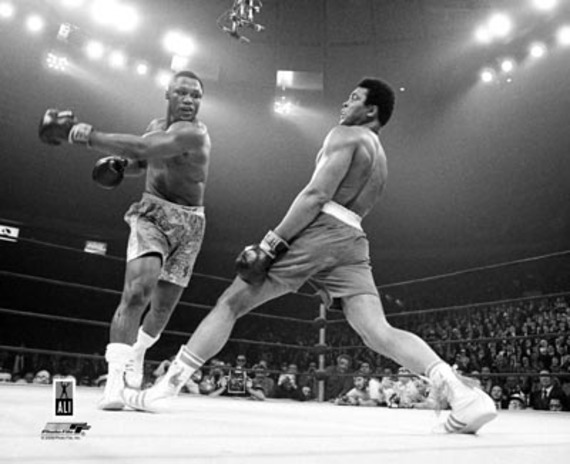

In 1971, the US Supreme Court overturned his conviction in a unanimous and historic 8-0 ruling, and Ali made his comeback for the championship against Smokin’ Joe Frazier, the tough and furious champ who had taken Ali’s place in his absence. Held on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden in New York City, “The Fight of the Century” transcended sports and divided the fan base in two. If you were for Frazier, the current champ, undefeated at 26-0, 23 KOs, you were part of the white, conservative establishment of America. If you for Ali, now the challenger and also undefeated at 31-0, 25 KOs, you were probably some combination of black, young, liberal, against the Vietnam War and for the Civil Rights movement. There was no doubt which side I was on as I watched the closed circuit fight on a giant screen in the downtown Chicago sports arena, filled with thousands of rabid fans who had waited an eternity for Ali’s comeback and retribution.

I have never been, before or since, to such an emotional or volcanically eruptive event. Not in another sports arena, not in a World Cup, not anywhere. The fans, no matter who they were for, were on their feet the entire fight. We felt every punch, were rocked with every body blow, every lightning left jab from Ali, every punishing left hook from Frazier. By the start of the 15th round, the fight that had gone the distance and more than satisfied any of our greatest expectations. The referees score cards were close, but Frazier had been dominating the last several rounds, driving Ali back into the ropes with his relentless and brutal power. Lesser fighters would have just not answered the bell; both Ali and Frazier had absorbed so much punishment from each other that it was hard to believe they were each standing when they touched gloves for the final round. It was a truly a fight between two undefeated champions.

But then the impossible happened. In the 15th round, Frazier caught Ali with a spectacular left hook that put Ali on his back. Ali, jaw swollen grotesquely, got up quickly from the blow, and managed to stay on his feet for the rest of the round, but a few minutes later… the judges made it official: Frazier had retained the title with a unanimous decision, dealing Ali his first professional loss. What the…? How could it be? Our hero defeated? The one and only Ali conquered by Smokin’ Joe? It was hard to take. Painful. But Ali himself said soon after the fight: “I’m not going to cry. I made a lot of people unhappy when I beat them, so it’s my time now. A lot of great fighters get whipped. No one can hit as hard as Frazier. I’m satisfied with the fight even though I lost. I know I lost to a great champion, but maybe another time when both of us had been fighting regularly, the result would have been different. I don’t know, but maybe.” Fair and honest words… but still… hard to swallow.

As we know, Ali got his chance for revenge upon Frazier… twice. The first rematch, fight number two of the three great historical fights between them, was also fought at Madison Square Garden in New York City on January 28, 1974. At the time, Frazier had lost his heavyweight title to the George Foreman, the jolly giant of a champion, whose legendary and lethal punches were feared throughout the sport. Foreman had grabbed the title from Frazier in 1972 by pummeling him senseless, knocking him down 6 times in the first two rounds before the fight was stopped. But Ali still wanted to avenge his 1971 loss to Smokin’ Joe, and on this night, he did… in a unanimous decision… thwarting Frazier’s inside power by consistently grabbing him behind the neck with his left hand while tying up Joe’s punishing left hand with his other. It was yet another example of Ali’s hand and foot speed, endurance, and tactical boxing skills. And the Reaper and I were ecstatic with the outcome.

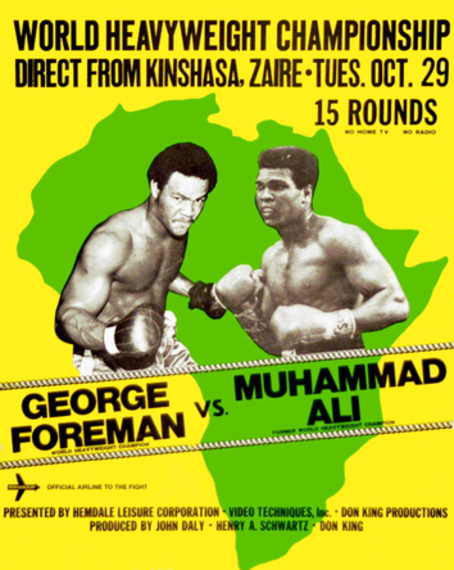

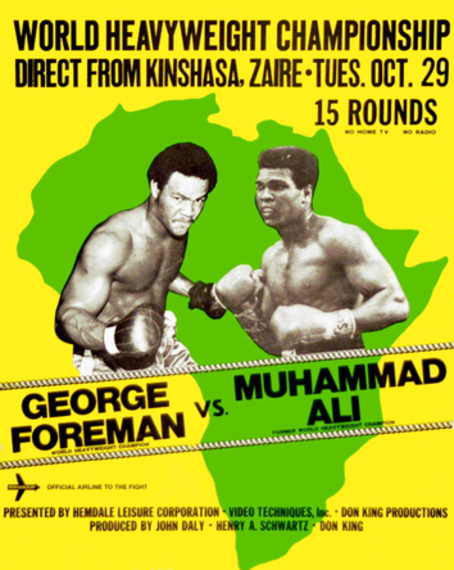

Yet Ali still had two legendary fights in front of him. The first of the two was the “Rumble in the Jungle”, fought against the fearsome Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo).

Held at the 20th of May Stadium on the night of October 30, 1974, it pitted the current undefeated world heavyweight champion, George Foreman, against challenger Ali, still waiting for this shot to regain his championship belt. Foreman was a fierce, terrifying, and powerful boxer, a force of nature. A huge man who couldn’t be beat. The fight was held at 4 a.m. in the morning Zaire time, broadcast closed circuit back to the States in prime time, and was promoted by the eccentric, electro-Afro-haired, Don King. It has been called “arguably the greatest sporting event of the 20th century”. Captured in the Academy Award winning documentary film, “When We Were Kings”, the fight and its electric buildup once again transcended sports, because at this moment in time, Ali was inarguably the most famous and recognized man on the planet. Known to Muslims and Westerners alike, Ali’s handsome face, his larger than life personality, his athletic prowess, and especially his having defied the American government’s draft and its war in Vietnam, made him a hero around the world. Before the fight, Zairean people chanted “Ali, Boomaye!” (Ali, kill him!) everywhere he went, and we back home in America, at least The Reaper and I, joined in whenever we could.

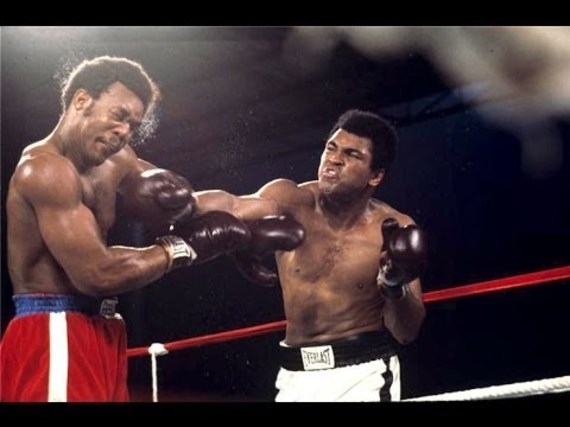

The fight was itself was all spectacle. Ali went in as a huge underdog. Word in the press was that Foreman’s raw punching power would annihilate the slighter Ali, hero, speed or no. But Ali went in with a tactical plan, soon to be called his famous “Rope-a-Dope” in the hard to believe aftermath. From the 2nd round on, Ali leaned back against the ropes and covered up is body and face with his elbows, forearms, and gloves. He allowed Foreman to pummel him with all his strength, which Foreman did, often landing tremendous blows, but never actually hurting Ali. By the 8th round, Foreman’s face was puffy from Ali’s lightning-fast left jabs, and more importantly, Foreman was “punched out”, entirely spent. No matter how many blows Foreman landed, Ali would come out of his “peek-aboo” defense and taunt Foreman: “They told me you could punch as hard as Joe Louis. That all you got, George?” Foreman would say afterwards: “I realized that this fight ain’t what I thought it was.”

In the 8th, Ali pounced as Foreman tried to pin him on the ropes. Ali landed several right hooks over the exhausted Foreman jab, followed by a 5-punch combination, culminating in a left hook and a hard right straight to the face that brought Foreman to the canvas. Reaper and I jumped out of our Madison Square Garden seats and screamed our lungs out… along with the rest of the unbelieving crowd. This couldn’t possibly be happening! Ali knocking Foreman down? “Ali! Boomaye!” Giant George got up slowly at the count of nine, woozy, but referee Zack Clayton stopped the bout with two seconds remaining in the round. The fight was over! Ali had won by knockout (TKO) and regained the heavyweight championship of the world. It showed that he could take a punch with the greatest of champions and that his tactical genius, changing his fighting style with the rope-a-dope, instead of his constant movement to counter other opponents, truly made him “The Greatest” of all time.

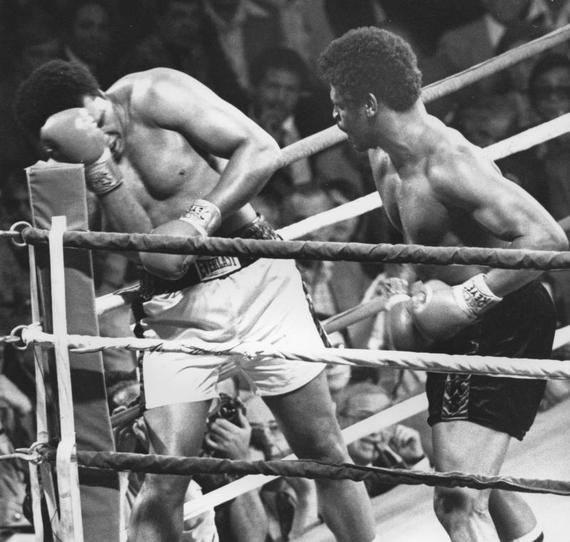

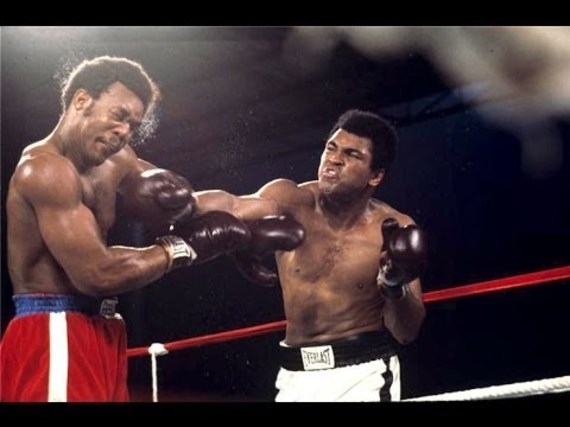

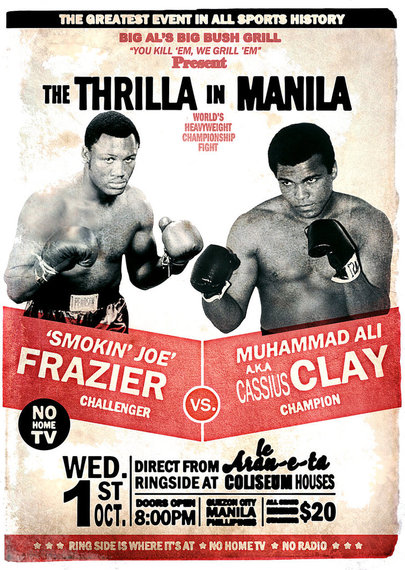

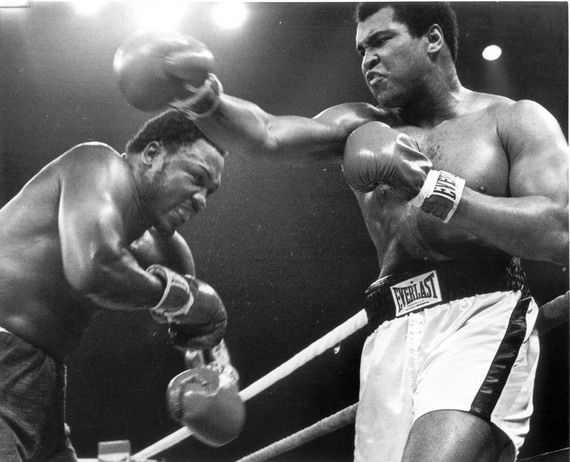

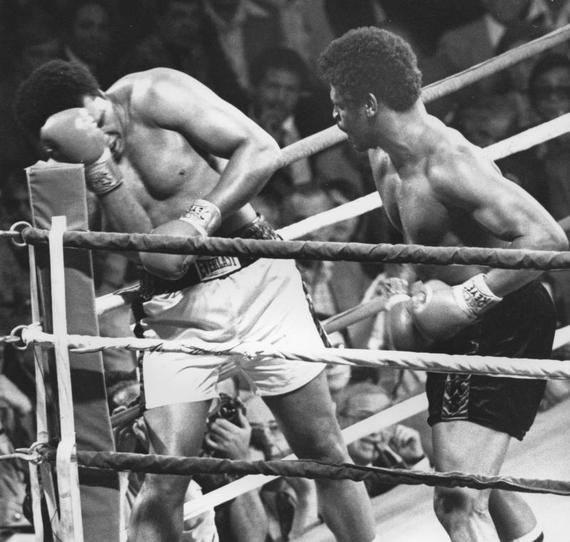

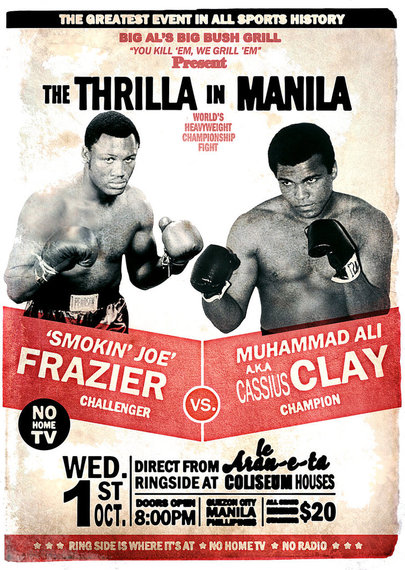

Next was Ali’s last great triumph… the third and final fight against Smokin’ Joe Frazier, in the aptly named, “Thrilla in Manila”, also unanimously considered one of the greatest fights in boxing history. Fought in Quezon City, Manila, Philippines on October 1, 1975, this was the “rubber match” between Frazier and Ali, two of the sports all time greatest champions. “It will be Killa and a Thrilla and a Chilla When I get the Gorilla in Manila.” Once again, the pre-fight build up was tremendous; no one could promote a fight, or taunt his opponent, like Ali. Only Ali could fill boxing arenas around the world. Fights no longer had to be held in las Vegas of New York City; they could be held anywhere in the world and Ali’s fame and popularity could guarantee that the arenas would be sold out.

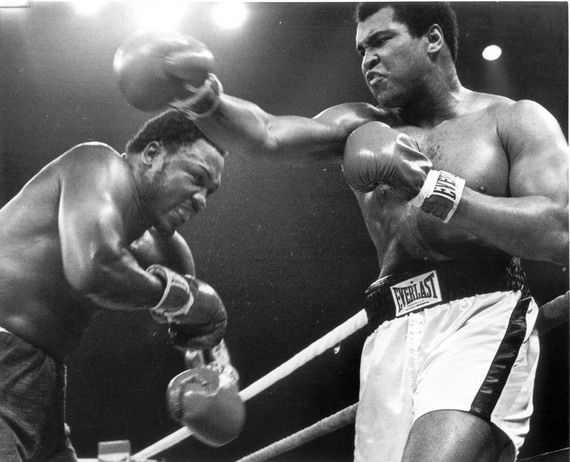

The fight began at 10 a.m. local time, and it was an evenly matched, brutal fight. By the end of the 9th round, Frazier’s face was swollen almost beyond recognition, and Ali had weathered some of the most powerful punches he had ever taken. “Man, this is the closest I’ve ever been to dying,” Ali was overheard saying to corner man, Angelo Dundee. British sports writer, Frank McGhee, sitting ringside for the Daily Mirror describes the final rounds:

“The main turning point of the fight came midway through the thirteenth round when one of two tremendous right-hand smashes sent the gum shield sailing out of Frazier’s mouth. The sight of this man actually moving backwards seemed to inspire Ali. I swear he hit Frazier with thirty tremendous punches – each one as hard as those which knocked out George Foreman in Zaire – during the fourteenth round. He was dredging up all his own last reserves of power to make sure there wouldn’t have to be a fifteenth round.”

Frazier didn’t go down. However his trainer, Eddie Futch, seeing how battered Smokin’ Joe was by the end of the 14th round, decided to stop the fight between rounds rather than risk a similar or worse fate for Frazier in the 15th. Frazier protested stopping the fight, shouting “I want him, boss,” trying to get Futch to change his mind. Futch replied, “It’s all over, Champ. No one will forget what you did here today”, as he signaled to referee Carlos Padilla, Jr. to end the bout. It was over. Ali had won. But at what cost? Both men had taken such a beating from the other that it was indeed, hard to watch. Most of all though, besides which man you were rooting for to win the fight, it was truly amazing to witness the hearts of these two great champions.

After that fight, Ali fought some more. But he was never the same. That was his pugilistic peak. Then in December 1981, the great Ali retired from boxing. Three years later in 1984, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Syndrome, a debilitating and humbling disease robbing a person of motor function and speech, most commonly brought on by severe head trauma, such as that experienced in a boxing ring. It could be said that like many great boxing champions before him, Ali didn’t know when to quit. He fought long after his incomparable boxing skills and powers had been diminished, losing some bouts to lesser fighters, and particularly taking a severe physical beating and his only knockout loss from champ, Larry Holmes, his former sparring partner.

It is sad and painful to see images of the great Muhammad Ali disabled by Parkinson’s. We’ve seen him light the Olympic flame at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, and he was the titular bearer of the Olympic flag in the 2012 Summer Games in London, where he was helped to his feet by his wife, Lonnie. But despite his sad and painful physical decline, Ali is still one of the most recognizable and beloved human beings on the planet, over 30 years after his exit from the world of competitive sports. Just go to his Facebook page (

https://www.facebook.com/MuhammadAliVerified) to find evidence… where over five and half million people follow his inspirational daily posts.

Childhood heroes never die though. They last forever. And for me and The Reaper… Muhammad Ali, nee Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky… will always and forever be… the one and only….eternally… “The Greatest”.

———————————————

Travel the world with “e-travels with e. trules” blog

Become a Subscriber of his Santa Fe Substack.

Listen to his travel PODCAST

Or go to his HOMEPAGE

Eric Trules’ Twitter (X) handle: @etrules