cowboys and samurai, exploding the myth

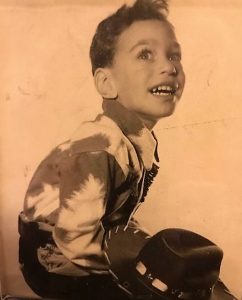

i usedta be a cowboy. when i was 5 years old.

i had a gray and white flannel western shirt, blue jeans, and baby brown cowboy boots. my eyes were pure blue, clear, and innocent, and i tried to be a good boy and to do everything my parents wanted. i watched all the cowboy shows on tv in the 50s and 60s.

i was a fan of lash larue, the cisco kid, and hopalong cassidy.

the rifleman,

brett maverick,

the lone ranger,

davey crockett, andy devine, and richard boone as a bounty hunter, “paladin”, in “have gun will travel”.

not so much gene autry, one of “the singing cowboys”, along with roy rogers.

and my mom didn’t let me stay up late enough for “gunsmoke”.

as i got older, i saw “shane”, “high noon”, “the man who shot liberty valance”, “red river”, “shootout at the ok corral”, “cat ballou”, “bad day at black rock”, “the gunfighter”, and “how the west was won”.

a suburban new yawk intellectual jewish kid from longisland, i was taken in by the american west and the myth of the trailblazing, pioneering cowboy. he was always in the right. he fought bad guys, savage “indians”, drunks, outlaws, and interlopers of all kinds. he was the chin-jutting sherriff, the ice-in-the-veins marshall, the fearless but persecuted homesteader, the immaculate justice-toting gunslinger.

he was wild bill hickok, wyatt earp, buffalo bill cody, doc holliiday, billy the kid, jesse james.

wild bill hickok

even when he was bad, he was good. i had all kinds of toy six-shooters, a cowboy mural on my yellow pastel bedroom wall with a hand-painted corral and a bucking bonc, and i had the complete, 80 card, 2 set editions of davey crocket cards. i still do, somewhere in one of my old camp trunks.

_________________

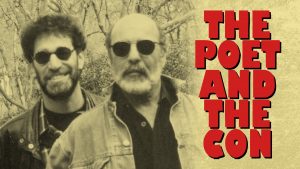

then in an odd family twist of fate, i discovered that my favorite uncle, my mother’s youngest brother, just 13 years older than i was, turned out to be “an outlaw”, a real-life “criminal. part of 3-person team who were the most notorious and most successful burglars in california, my uncle harvey was also a strong man for the jewish mob and lived a full life of crime. he even knew the infamous jewish gangsters, meyer lansky and bugsy siegel. he ended up spending more than half his life in prison, but even after he was released, his past caught up with him and he ended up profiled on “america’s most wanted” and charged with “murder for hire” in judge lance ito’s courtroom, just before judge ito was appointed to the o.j. simpson trial.

i made a film about my relationship with my uncle harvey (rosenberg) called “the poet and the con”. it took me seven years to make, and you can google it or find it find it online on its own website.

in any event, it was not long after my loss of innocence, that my identification with my criminal and outlaw uncle, with the childhood tv cowboy shows having sadly faded into my fickle memory, that i came to realize the de-constructionist truth.

that the spanish and european conquistadors (romanticized “cowboys of their own era) – columbus, cortez, pizarro, etc.

– the high and mighty “fathers” of our hemisphere – had instead – virtually raped the land, annihilated the native people, and destroyed the culture – to establish omnipotent colonial power in the americas.

that they had enslaved and corralled the indigenous people, eradicated a majority of them with european disease, and brainwashed them and forced them into practicing rigid european chrisitanity.

i was shocked. how could it be that neve

r in miss bandiero’s 11th grade american history class, which i loved so dearly, did we never learn that the frontier american government cruelly and disingenuously repeated the same humiliating scenario as the original european colonizers? oppressing and exploiting the native american “indian” population, breaking treaty after treaty, and wiping out the majoriity of the native population with disease, encarceration, and military superiority.

sure, tonto was the lone ranger’s safe and wise indian tv sidekick, but cochise, crazy horse, sitting bull… these were all real indian chiefs… who fiercely fought and opposed the american government’s domination and genocide before their hearts were so brutally buried at wounded knee, south dakota.

and my main man, fess parker, who played tv’s davey crockett, and wyatt, and jesse, and the bills, these were some tough and bitter hombres who, along with upholding the law, also no doubtedly broke it repeatedly, killing good guys, bad guys, “indians”, outlaws, and who knows who else in the not always justice-keeping and re-written history of the american west.

————————————————–

then i went away to college. buffalo, new york. (an unconscious homage to the bills?)

and there i met professor norman holland. and his language and aesthetics of film.

i fell in love anew.

with the samurai.

and of course with toshiro mifune in “yojimbo” and “sanjuro”, and with all of kurosawa’s “seven samurai”, but also with inagaki’s “samurai trilogy”, and the blind but prolific swordsman, zatoichi.

the samurai was a more sophisticated symbol for me to identify with and to romanticize. he was a loner. he was disciplined, both ascetic and aesthetic. a warrior. never would a woman interfere with his quest. his job. his higher principles. he was a trained and ritualistic fighter. a swordsman.

not just some hotheaded cowboy with a gun.

sure, he was a paid mercenary, but he did have some discretion as to who he would defend, who he would accept money from.

i wanted to be a spiritual and life-long warrior.

i wanted to be a samurai.

so i went through my young adult years as a samurai.

well, not exactly. but as an artist.

first, as a modern dancer.

i trained every day. i was disciplined. i had artistic, ascetic, and aethetic principles.

i lived for my art. not money. i sacrificed.

i didn’t get tied down to women. i was free. free to move on when and where i wanted to.

i tried to be strong. honest. principled.

then i became a clown. a professional one.

samurai, you ask?

well, yes. i was still disciplined. i trained at and taught what i did. i lived on 100 dollars a week, if i was lucky. i made people laugh, sacrificing my own nobility and pride.

look at mifune in early kurosawa samurai movies. yojimbo. sanjuro. he was a fool. he flopped, fought, raged, and drank. a samurai clown if ever there was one.

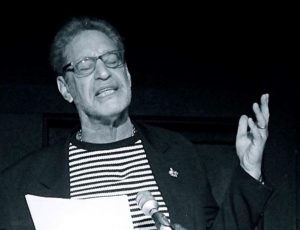

then i became an actor. a solo performer. dependent on myself. my own words.

i put myself out in the universe and demanded to be heard. to be seen.

i failed many times. i succeeded many others.

it was a constant challenge. a constant battle, being an artist.

so little support or encouragement from my culture. from my government. a constant financial struggle. but i was on the path. some western samurai-warrior path of being an artist. demanding the most of oneself. never compromising. a purist. a clown. an outsider. a dying breed.

my youth passed. dancer, clown, solo performer, teacher…..

i was in my 40s. living in LA.

in 1969, i had gotten myself arrested in deadwood, south dakota, long before mr. milch and HBO discovered it – for wreckless driving. i spent time in wild bill hickok’s jail, and i was chained to the mountain-sized indian, neck. i was released on bond and never returned for trial. perhaps i’m still wanted in them thar black hills of south dakota.

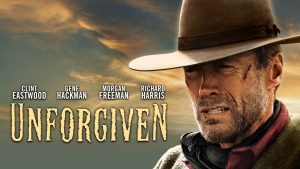

anyway, in 1992, clint eastwood made the movie “the unforgiven”. it was dark and ornery, and there was something specifically about it that quickly put it atop my all-time list of cowboy movies.

what was it, you ask?

it was – the killing.

specifically, how hard eastwood made the killing.

no longer were cowboys just firing bullets into the bodies of their enemies; no longer was a single quick-on-the-draw gunslinger just firing and wiping out whole crews or families of james-es, billies, or willies.

no. because here was legendary gunfighter, william munny, taking on one last job. for the money. not for the glory. not for revenge. not for truth, justice, or the american way.

no, but just for survival.

a cowboy who’d lost his wife, who was no good at farming, and in fact no good at anything but — killing.

and now, an old man, he’s not even up for that. yet here he is, riding off to the town of big whiskey to kill one more time.

finally, the movie has munny do it.

kill, not heroically, but painfully, and in the process, eastwood forever blurs the lines between heroism and villainy, between man and myth. squeezing the trigger of a gun, staring a man in the face whose life you’re going to take, would never again for me be an act to celebrate.

and then there’s the great gangster movies, and in our time, the godfather trilogy and 8 years of the sopranos.

i mean, here’s vito corleone and tony soprano, mafia dons both, following the infamous trails of al capone, bugsy siegel, and all rest of the fictional and real cold-blooded killer-inheritors of the american west.

killing for family. for honor. for greed. killing for power, sex, money; killing for killing sake. and here we are, the adoring and mesmerized public, waiting with each baited scorsese breath for the next gangland execution. the next garroting. the next bullet riddling. the next brutality. all in the name of entertainment.

and now i’m 59. 60 next month.

life’s been moving along. my hip’s bad.

i’m still teaching and i’m going to china next month on another adventure.

last night i rented “harakiri” on netflix, and all over again, i’m put in touch with the power, the restraint, the beauty of japanese samurai culture.

it’s 1630. beginning of the centuries-long institution of samurai. of seppuku.

it’s the story of 2 down-on-their-luck feudal samurai who have lost their job fighting for their sponsors. it’s a time of peace, and once again, these trained mercenaries can’t farm or live without the sword. they suffer in poverty. and they come to the ruling clan of samurai with a favor to ask.

can they commit harakiri (“seppuku”, the painful bowel dismemberment ritual) in the ruling samurai’s courtyard?

thinking first that the son-in-law, then father-in-law, are not serious about their requests, but only trying to be sent off with some money in their pockets, the ruling samurai force the 2 men to commit harakiri.

the younger man doesn’t even have a steel blade; he is forced to do so with a bamboo sword, with which he naturally does a messy and painful job.

enter the father-in-law. played by the fierce-eyed nakadai tatsuya.

he is told the brutal story of his son-in-law’s harakiri and asked if he still wants to go through with his own. without acknowledging his relationship with his son-in-law, he agrees to it.

but not before telling his story.

an amazing one – in which he first tells of his son-in-law’s heroic sacrifice of selling his samurai sword for a bamboo one in trying to save the life of his wife who is in a difficult labor without doctor or medicine.

that is why he shows up to commit harakiri with a bamboo sword.

but the proud and stubborn samurai clan don’t want to hear any whys. they only want to carry out the harakiri and not be taken for easy touches.

next, after throwing down 3 small, wrapped packages on the seppuku mat, the father-in-law tells of how he tracked down 3 members of the ruling samurai clan, the 3 who witnessed his son-in-law’s brutal self-execution.

he tells of his individual encounters with each, as he subjugates each in battle and rather than kill his opponent, he instead humiliates each man by cutting off the “top knot” from his head, thereby allowing his hair to fall down “like a woman”.

the samurai clan leader, who has been patient enough to hear the father-in-law’s long story, is outraged that 3 of his men not only have been beaten by a “starving country ronin”, but that they have lied about their lack of appearance at the ritual.

he orders the father-in-law to be chopped down. but the father-in-law kills 4 samurai with great courage in a final battle with the entire clan, and he has to be shot down before he is conquered and vanquished.

in the end, the samurai leader lies and makes sure that none of the heart-breaking truth is recorded for posterity.

for it is far better to lie, thereby keeping one’s dignity and reputation, than to have empathy for a opposing samurai or to record the truth.

to my surprise, “harakiri” quickly replaced all the other samurai movies i had ever seen as my favorite. because of its power. its discomfort.

it was, in fact, an “anti-samurai” movie. much like “the unforgiven”, “harakiri” was an anti-violence movie.

it uncovered the truth underneath the all-powerful, unblinking samurai myth, and showed it to be a sham.

just as hopalong cassidy and the lone ranger were ultimately made-for-tv kiddy entertainments, and most probably wild bill hickok, wyatt earp, and bat masterson were far from being the ideal heroes of cowboy lore, and just as vito corleone and tony soprano were finally only brutal thugs with colorful families and photogenic, senisitve sides, so were these impeccable samurai finally and merely human, vain, and ignoble.

it’s nice to walk around inside the memories of childhood.

i have a synthetic, racoon-tailed davey crockett hat signed by fess parker, the disney actor, that i got on a trip to his medocino self-named winery.

one day, maybe i’ll dig into my old black camp trunk to find my perfect, 2-set, 80 card davey crockett collection.

in my mind, i can always go back to that yellow-painted, bucking bronc mural in the old westbury of my youth.

maybe even one day, i’ll drive back through the sacred black hills of south dakota to see if there’s actually still a warrant for my arrest in 1970 for “jumping bond” and not returning for trial.

but after watching and re-watching “the unforgiven” and “harakiri”, never again will i want to be a cowboy or a samurai.

it’s hard enough being myself.

Travel the world with “e-travels with e. trules” blog

Become a Subscriber of his Santa Fe Substack.

Listen to his travel PODCAST

Or go to his HOMEPAGE

Eric Trules’ Twitter (X) handle: @etrules